Lassa Fever: An emerging viral disease

1. Introduction

The control of Lassa fever is challenging due to the lack of sensitive and specific diagnostic testing, along with non-specific symptoms. Early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment improves survival. Furthermore, because of the many asymptomatic or mild infections, only a proportion of expected cases come in contact with health services, leading to a gross underestimation of the number of cases. In this review, we will analyze important recent advances on Lassa fever. Epidemiology, determinant factors on the severity of the disease, including organ transplant-related Lassavirus infection, together with current public health recommendations and future perspective, will be discussed.

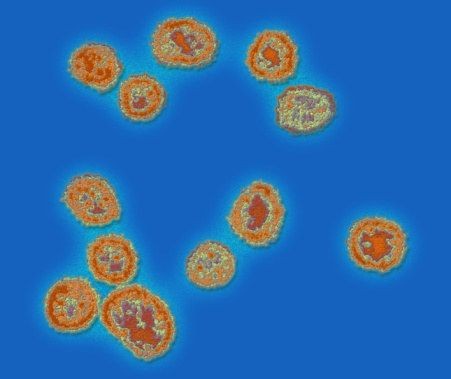

Lassa fever is an acute viral illness that occurs in West Africa. The illness was discovered in 1969 when two missionary nurses died in Nigeria, West Africa. The virus is a single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) virus belonging to the virus family Arenaviridae. The overall mortality is about 1%, while up to 15-20% can be observed during epidemics. Lassa fever is transmitted to humans via contaminated food or household items, or rodent urine or droppings. The disease spreads from person to person through direct contact with body fluids or secretions. During the Lassa fever epidemics, human-to-human transmission has been associated with hospital settings.

2. Causes and Transmission

Humans can create food contact by exposing the feces, blood, tissues, or urine of the infected rodent. Infection can also spread by ingesting contaminated food or household items. Lassa fever can also spread through direct contact with body fluids such as urine, saliva, feces, vomit, serum, blood, breast milk, sexually transmitted liquids, and other body fluids of an infected person. Human-to-human infection occurs frequently in healthcare centers and traditional health facilities, particularly in tasks performed during labor. Some epidemiological reports show that the disease spreads through sputum, urine, sweat, or a suspected aerosol, such as laboratory workers. Infection can spread by ingesting contaminated food or domestic items, such as a collapsed residence, a village market, a supply vehicle carrying infected rodents, or a traditional African attic residential stop. Only a few cases have been reported in laboratory conditions for patients who do not show convalescent antibody increases during an outbreak. Administration, iatrogenic transmission of nosocomial spread, or infection before discharge of Lassa fever patients have been recognized as a healthcare illness. Eventually, chat guard is crucial to prevent the spread of Lassa fever, and minimizing interaction with infected rodents and people who may carry Lassa hostages. Only biosecurity measures should be adopted when immunocompromised patients, a severely ill patient, significant organ dysfunction, especially under a ventilator, are associated with a central line oxygen mask.

Lassa fever is caused by an arenavirus named Lassa virus. It is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Arenaviridae family. Dermik Niazi first isolated the virus in 1969 from the case of a nurse in Lassa, Nigeria. It can spread in an African rodent Mastomys natalensis, which is a known host of the virus. Human Lassa originates from direct or indirect contact with contents, especially for the consumption and preparation of food. The reported death rate in hospitalized patients ranges from 15% to 20% with a high death rate in patients with ineffective symptoms, and in untreated cases, the death rate is relatively high.

3. Symptoms and Diagnosis

The high mortality rate recorded in 2018 (26%) is a source of concern and indicates that the virus is still a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. These results are particularly indicative of the need for the development and implementation of control and prevention measures that constitute the integrated system of the control and prevention of hemorrhagic fevers in West Africa. Lassa fever, which is one of the most important viral hemorrhagic fevers in humans, is an illness that varies in severity from mild to severe disease at risk. A first clinical diagnosis of Lassa virus infection is difficult since the fever is accompanied by multiple signs and symptoms (not specific) such as fever, headache with severe frontal pain, back pain, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, sore throat, rash, pneumonia, hallucinations, and meningitis. The hemorrhage may also occur, most often in the gastrointestinal system underlying the late stages of the disease. The Lassa fever virus is a family of Arenaviridae and can cause bleeding, hypertension, hypotension, pericarditis, and retrosternal pain. The symptoms may appear after 6-13 days. The main diagnostic methods are the detection of viral RNA, the detection of antigens, and the viral culture.

The majority of Lassa fever virus infections remain silent. The onset of the disease after the incubation period may be gradual with fever, headache, pharyngitis, myalgias, petechiae, chest and abdominal pain, and pleuritis. In 25 to 50% of cases, the disease manifests itself by pharyngitis, conjunctivitis, chest and abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and sometimes gastroenteritis. To date, only two deaths have been documented. Other symptoms may appear following the disappearance of fever and represent serious signs leading to death, which may occur 1 to 3 weeks after infection. At the same time, the disease improves obviously by aseptic meningitis. Symptoms may include nuchal rigidity, focal brain lesions, and convulsions. The last phase may end after several weeks with hearing loss, aphasia, and minor neurological disorders.

4. Treatment and Prevention

Prevention of Lassa fever depends on promoting good “community-based” control programs in the endemic areas. Public awareness is raised by social mobilization methodologies, communicative health education, and informative advertisement campaigns. Lassa fever prevention and care strategies must rely on some in-service training programs for families, health personnel, health employees, and nurses. Equipment handling, by adopting infectious control protocols and using proper safety measures to cope with sick patients. LHF exposure may be decreased by promoting sanitation and health procedures, raising public consciousness by supplying the Lassa fever and precise medical care supervision of infectious reservoirs. To stop or minimize the transmission of Lassa fever, precautions should be taken and actions carried out at the local, state, federal, and global levels. Controlling rodent poisons and relevant tools will decrease Lassa fever infections in endemic areas.

At present, there are no vaccines available for prevention and no specific therapy for post-exposure prevention from Lassa fever. Supportive therapy, trifluridine, ribavirin, and rVSV vaccination have proven to be successful for post-exposure preventive treatment modalities. 80mg/kg of ribavirin is administered intravenously to the patients with confirmatory test results of the virus, administered for 4 days, and later oral administration of 20mg/kg dosage for the next six days. It significantly lessens the disease fatality risk. The understanding of LHF expression in human beings and animals, dissection of the LHF transmission, the role of increased community exposure to Lassa fever, and the distribution of ecological Lassa fever reservoirs for infection in natural plants are all essential for disease control.

5. Conclusion

The problem of dilapidated health infrastructures and obsolete logistic systems pose the greatest challenge in prevention and control of Lassa fever. The recent outbreak of Lassa fever in Nigeria has revealed a number of issues including poor system of notification, response and preparedness. So far, there have been no proper data available on this disease. This is an alarming situation not only for Nigeria but also to the neighboring countries in Africa. The potential outbreak of Lassa fever threatens the lives of health care workers who are in close contact with the patients. Therefore, wearing a protective personal equipment (PPE) to prevent nosocomial transmission is highly recommended. In addition, educating the appropriate preventive measures against Lassa virus is crucial. Also, it is important to train hospital medical staff including community and family care providers on the preparedness and response to possible outbreaks of Lassa fever. Government institutions with public health authorities should put together efforts in educating the public as well as private hospital care workers about this highly infectious disease.

Lassa fever is caused by a hemorrhagic Lassa virus that is genetically related to the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). Like other isoforms viruses, the incubation period of the Lassa virus ranges from 6-21 days. Lassa fever in pregnant women during early trimesters leads to miscarriage and premature labor. Both live and dead fetuses retained in the uterus lead to maternal mortality. Neonatal complications are rare and can occur in the first five postnatal days. Lassa fever is an emerging and re-emerging zoonotic disease. Clinical symptoms are not different from other febrile diseases. Diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms and laboratory tests, since there are no pathognomonic signs.

Useful article. With learning Trading Tips you can earn more money and build your life better, to read a lot of useful free tutorial about this topic see https://mohammadtaherkhani.com website.